What Violence Leaves Behind

Bondi, collective grief, and the quiet costs carried by communities

In the wake of the tragic events at Bondi, the loss of innocent life weighs heavily on the entire community. An act of violence at a place of gathering and remembrance is devastating and unjustifiable, and the harm done to those directly affected must remain at the centre of our grief.

Alongside this collective mourning, a quieter tension also settles into the bodies of many Muslims. It is not always visible, but it is deeply felt. For many, this tension exists alongside sorrow and condemnation. It is shaped by an awareness that moments of public violence are often followed by suspicion, scrutiny, or blame that extends far beyond those responsible.

A Broader Climate of Rising Hate/Intolerance

Online, there has been significant discussion about the rise in antisemitism in Australia, particularly since the Israel–Palestine conflict escalated in late 2023. This concern is both valid and urgent. Jewish communities have experienced a sharp increase in threats, harassment and attacks, with community organisations reporting antisemitic incidents rising several hundred per cent compared to previous years. The loss of safety and security for Jewish Australians must be taken seriously.

However, it is critical to recognise that this rise in antisemitism is occurring alongside a broader increase in hate and intolerance across Australian society. Islamophobia has also risen significantly since the Israel–Palestine conflict, with data from the Islamophobia Register Australia showing that reported anti-Muslim incidents more than doubled in the months following October 2023. Muslim women, particularly those who wear the hijab, have been disproportionately targeted through verbal abuse, intimidation and online harassment. Anti-immigrant rhetoric has similarly intensified, reflecting a growing hostility towards those perceived as outside white cultural norms.

This broader climate of hate was visible in the large anti-immigration rally held a couple of months ago, where neo-Nazi figures were openly involved in speaking and organising. It is also reinforced through the popularity of politicians such as Pauline Hanson, whose political influence has long relied on stoking fear, division and suspicion towards migrants and Muslim communities. While antisemitism demands urgent attention, it does not exist in a vacuum. Islamophobia, antisemitism and anti-immigrant hostility are interconnected expressions of a wider erosion of social tolerance in Australia, one that places multiple minority communities at heightened risk simultaneously.

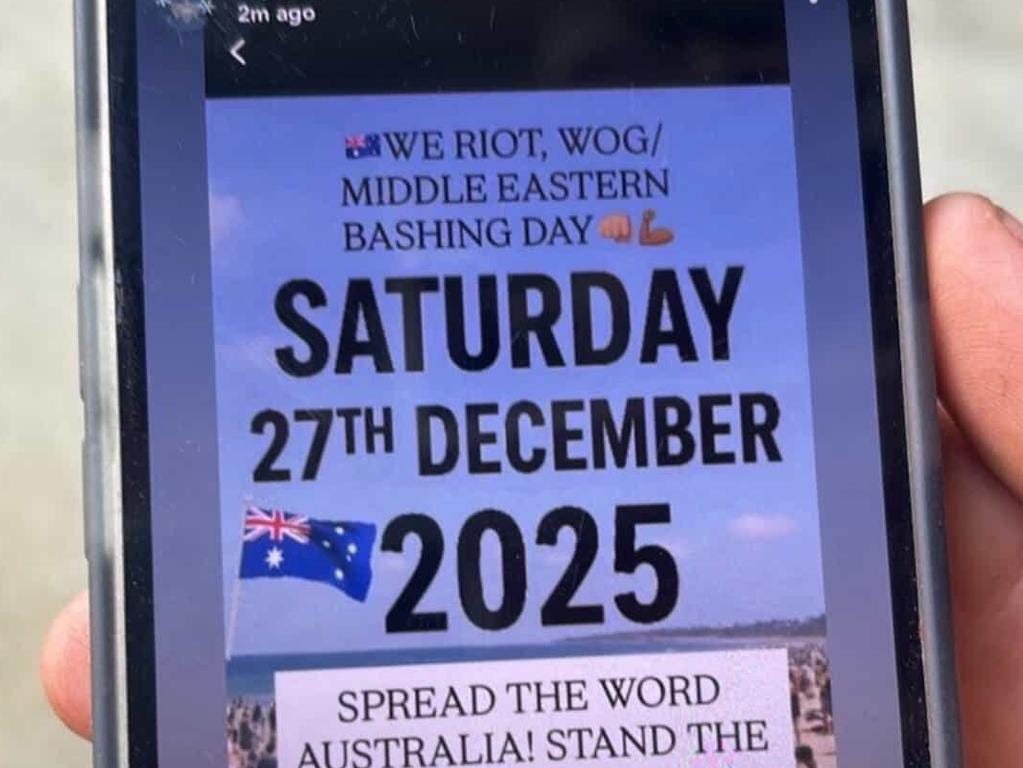

In the days following the mass shooting at Bondi Beach, social media posts calling for “wog” and “Middle Eastern bashing” began circulating widely, explicitly invoking mob violence and racial targeting. For those who know about the Cronulla riots in 2005, the language is not abstract. It is a reminder of how quickly public grief can be redirected into racialised rage. While police and political leaders have condemned the posts and promised swift action, the emotional impact has already landed. For people from migrant and visibly non-Anglo backgrounds, even ordinary acts like leaving the house or going to the beach now come with an added layer of calculation. What is most confronting is not only the threat itself, but the realisation that this kind of indiscriminate hostility remains close enough to resurface, especially in moments of national shock.

Scapegoat Politics

When examining politicians such as Pauline Hanson, one pattern becomes clear: her political influence is sustained through division, fear, and scapegoating. Hanson repeatedly mobilises moments of social anxiety, such as the cost-of-living crisis or security concerns, and redirects them toward marginalised groups, particularly immigrants and Muslims. This strategy, known as scapegoat politics, involves identifying a visible out-group to blame for complex structural problems, thereby simplifying public frustration into an easily targeted enemy. Rather than addressing systemic causes, fear is personalised and racialised.

Hanson’s rhetoric closely mirrors the populist strategies popularised by Donald Trump, including the use of slogans such as “Make Australia Great Again”, a phrase that functions as coded language for restoring an imagined white, exclusionary national identity. Online discourse increasingly reflects this shift, with such slogans circulating alongside anti-immigration, Islamophobic, and openly racist commentary. In this sense, political language does not merely reflect social attitudes; it actively shapes them.

Comments found under Pauline Hanson posts after just minutes of looking

This dynamic aligns closely with McQuail’s argument that the media does not simply report reality, but participates in constructing it. When political figures are repeatedly given media platforms to frame social problems through blame and fear, these narratives become normalised and absorbed into public consciousness. Over time, audiences may come to accept these interpretations as common sense, even when they rest on misinformation or racialised assumptions.

Anne Aly’s community victimisation perspective helps explain the social consequences of this environment. When political and media narratives repeatedly frame Muslims and immigrants as threats, entire communities experience collective suspicion and heightened scrutiny, regardless of individual behaviour. This produces anticipatory fear, where people expect hostility before it occurs, leading to withdrawal, hypervigilance, and fractured belonging. In this way, scapegoat politics does not merely divide electorates; it actively generates conditions in which minority communities are positioned as perpetual outsiders, responsible for social anxieties they did not create.

Selective Empathy in the Aftermath of Violence

What happened at Bondi was horrific and should never have occurred. The loss of innocent life is devastating, regardless of where it takes place. What has been particularly confronting in the aftermath of the Bondi attack is how quickly public discourse has shifted toward blame, deflection, and selective empathy. The loss of life is devastating and unjustifiable, regardless of where it occurs. Yet responses in the West often reveal a pattern where grief is amplified when violence happens close to home, while suffering elsewhere is met with indifference, rationalisation, or silence.

Sociologists describe this as moral proximity and hierarchies of human worth, where lives that resemble our own culturally, geographically, or racially are more readily grieved. This pattern reflects what Susan Sontag and later scholars of political violence describe as compassion fatigue and selective moral attention, where repeated exposure to distant suffering produces emotional numbness rather than solidarity. Death in Western cities is framed as shocking and incomprehensible, while death in places like Palestine is normalised, contextualised, or implicitly justified through political language. This uneven distribution of empathy does not reflect an absence of morality, but rather how global power relations shape whose lives are considered fully human and whose deaths are rendered ordinary.

This selective empathy is reinforced through broader processes of dehumanisation and othering, where violence against racialised or non-Western populations is framed as inevitable, self-inflicted, or politically necessary. Social identity theory helps explain how in-group identification strengthens emotional responses to “our” suffering while distancing us from the pain of those marked as outsiders. In Western contexts, this often manifests as a moral double standard: grief for victims at home exists alongside suspicion, blame, or outright hostility toward marginalised communities, particularly Muslims, when violence occurs. Anne Aly’s concept of community victimisation is relevant here, as entire communities come to anticipate backlash not because they are responsible, but because dominant narratives repeatedly position them as threats rather than mourners. At the same time, theories of structural violence remind us that ongoing harm outside the West is often invisible precisely because it is embedded in global systems of power, occupation, and inequality. When death becomes routine in certain places, it loses its capacity to shock. The danger of this desensitisation is not only ethical but social: it erodes our ability to recognise shared humanity and allows grief to be politicised, weaponised, and unevenly distributed.

Debunking the Islam–Terrorism Myth

One of the most enduring and damaging misconceptions in Western public discourse is the idea that Islam inherently supports terrorism. This claim is not only factually incorrect, but sociologically and psychologically flawed. Islamic doctrine does not legitimise the killing of civilians, collective punishment, or indiscriminate violence. On the contrary, core Islamic principles emphasise the sanctity of life, justice, and moral accountability. Acts of terrorism committed by individuals who identify as Muslim represent a profound violation of Islamic teachings, not their fulfilment.

Dr John Ali makes this distinction explicit by separating Islam as a faith from militant interpretations that instrumentalise religion for political ends. He argues that violence emerges not from Islam itself, but from the interaction of grievance, ideology, opportunity, and networks, often within contexts of exclusion, dislocation, and perceived injustice. Radicalisation is therefore a social process, not a religious inevitability. Many individuals who become involved in militant movements are not deeply religious to begin with, but rather seek meaning, belonging, certainty, or purpose in moments of personal or collective crisis.

The persistence of the “Islam equals terrorism” narrative is largely sustained through media repetition, political rhetoric, and securitised frameworks that flatten Muslim diversity into a single threatening identity. When violence occurs, and perpetrators have Muslim-associated names or backgrounds, entire communities become symbolically implicated. This produces this community victimisation, where Muslims anticipate suspicion and hostility regardless of individual behaviour. Over time, this collective scrutiny fosters fear, hypervigilance, and withdrawal, reinforcing the very social isolation that radical groups exploit.

Importantly, over-securitisation of Muslim communities does not prevent radicalisation; it risks exacerbating it. When Muslims are treated primarily as potential threats rather than citizens, trust erodes between communities and institutions. Dr Ali warns that constant surveillance, suspicion, and political targeting can intensify feelings of exclusion and injustice, particularly among young people navigating identity in pluralist societies. In these conditions, simplistic narratives offered by extremist ideologies may appear attractive not because of religious conviction, but because they offer clarity, a sense of belonging, and a moral purpose.

Psychological factors also play a critical role. Radicalisation pathways often intersect with identity crises, trauma, humiliation, and perceived loss of dignity, rather than theological devotion. The desire to defend a global Muslim “victim identity”, as Dr Ali explains, can motivate individuals who feel disconnected from both their heritage and their national belonging. When Islam is repeatedly framed as incompatible with Western values, some individuals internalise this exclusion, while others may react by embracing oppositional identities.

Equating Islam with terrorism is therefore not only inaccurate, but it is also counterproductive. It obscures the real drivers of political violence, legitimises collective punishment, and deepens the marginalisation of millions of ordinary Muslims who reject violence unequivocally. A more responsible approach requires dismantling essentialist narratives, resisting fear-based politics, and addressing the social, psychological, and political conditions that allow extremist ideologies to take root. Islam is not the problem; the problem is how fear, power, and exclusion distort both religion and response.

Choosing solidarity over suspicion

In moments of collective trauma, societies are often faced with a choice. They can retreat into fear, suspicion, and division, or they can respond with care, clarity, and solidarity. The aftermath of the Bondi attack has shown how quickly grief can be distorted into blame, and how easily entire communities can become implicated in acts they neither caused nor condone. Yet it has also revealed moments of resistance to this logic: voices insisting on nuance, shared humanity, and collective responsibility rather than collective punishment.

Interfaith dialogue and community engagement are not symbolic gestures in these moments. They are essential social practices that interrupt cycles of othering and scapegoating. When Jewish, Muslim, and broader community leaders come together to publicly grieve, condemn violence, and affirm one another’s safety, they challenge the false narrative that communities are locked in inevitable conflict. They reaffirm that grief is not a competition and that solidarity does not require sameness. These acts of connection help prevent the isolation and fear that extremist ideologies rely upon to grow.

Figures such as Ahmed al-Ahmed play a critical role in reshaping public understanding during these periods. By consistently rejecting the equation of Islam with violence and emphasising shared ethical commitments to dignity, life, and justice, he works to dismantle narratives that portray Muslim identity as inherently suspect. His interventions highlight that the most effective response to violence is not heightened suspicion or securitisation, but social cohesion grounded in trust, dialogue, and mutual recognition. In doing so, he reframes Muslims not as problems to be managed, but as active participants in building safer, more inclusive communities.

Ultimately, resisting hate requires more than condemning it. It requires refusing the stories that sustain it. Interfaith dialogue, community solidarity, and responsible public discourse offer a way forward that honours victims, protects vulnerable communities, and rejects the politics of fear. In choosing to come together rather than fracture apart, societies assert that violence will not define them and that no community should ever have to carry the burden of another’s crime.

That’s all from this chatterbox today.

With love, always,

Ari <3

The part about compassion fatigue!!